In the early 1980s, Harry Santamäki had a vision that gave rise to the world's first desktop-sized videophone. It enabled making calls and seeing the person at the other end of the line at the same time. “We made Skype as far back as 20 years before Skype”, Santamäki says with a smile.

Harry Santamäki describes himself as a ‘product guy’, since he has always been involved with new products. His interest in technology dates back to his childhood, when he was building all kinds of machines and equipment already at the age of four. In his school years, he had one vision only: to become an electronics engineer. And that is the path he also ended up following. Santamäki worked at VTT for 14 years before setting up his own spin-off company Vistacom, focusing on videophones.

What was a videophone all about at the time?

The invention behind everything was a satellite – a satellite that took pictures of space and printed them out. This way people became familiar with digital image processing, which was a brand new thing in the early 1980s. At the same time, VTT was also launching research programmes, one of which focused on image processing, involving many different laboratories.

Santamäki himself worked at a communications laboratory, exploring how to transfer satellite images. At that time, the telephone network's transfer rate was around 2–5 kilobits – when today a 10,000-kilobit connection is considered slow. Internationally, there were already different videoconferencing solutions around. They involved people sitting in a conference room gathered around a big screen with the image changing every 10 seconds. The systems made it possible to see who were present in the conference and to show slides.

“I got an idea. With digital technologies, the compressing of images was advancing so rapidly that it made me wonder what if it we could transfer live image with much smaller transfer rates. Back then, we still needed some sort of a special system, like a satellite connection, to transfer video image,” Santamäki says.

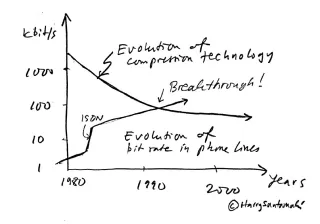

We knew that the digitalisation of telephone networks would begin in mid-80s, which would increase the regular network transfer rate by more than ten times. Santamäki drew a conceptual image. The ability to compress image and the telephone network's transfer rate would converge in five years’ time, making it possible to transfer sufficiently good live image via telephone lines in the same manner as usual voice calls.

From idea to implementation

The timeline for a videophone advanced quite smoothly. When the programmes relating to the technologies needed were launched in the very early 1980s, Santamäki's vision already existed. The videophone was introduced for the first time in 1984, in a major publication event, with even TV cameras present. It was an immense moment of success for the team. First, the public was shown the present situation in which the image changed every 10 seconds, as in a slide presentation.

“After that we pressed a button, and the person at the other end of the line suddenly went live,” Santamäki says with a laugh, reminiscing about the première of the videophone.

One year later, the videophone already featured a colour image, and two years later the spin-off company was established. Vistacom, focused on videophones, was in operation for five years in all.

Finger on the pulse, but too early

Santamäki and his partners, however, were way too much ahead of their time. The world was not yet ready for the introduction of a videophone. The same happened as with the regular telephone: people did not hasten to adopt the new technology right away. The device was largely sold to telephone companies for demonstration purposes only, and finally the recession of the 1990s and the internet buried the videophone.

This did not discourage the team as they set out to transfer the technology developed for videophones to be used in videoconferencing and desktop computer screens. In fact, Santamäki and his partners ended up establishing yet another company that grew very rapidly and gained success in the US in particular.

“But then in the mid-1990s we saw the coming of the internet. I suggested that we should adapt the videophone for the internet and just develop a software-based version of it for general use. But then came Skype and kind of ate our lunch,” Santamäki says.

Even though the invention did not really take wing, Santamäki would do almost everything in the same way – with one exception:

“It’s important to remain level-headed. If I had to do it all over again, on the second round, I would keep the invention to myself longer and not go around telling everyone about it, trying to get them excited about it as well.”

The process did not leave the team totally empty-handed either. It welded them together and helped build a company with 20 employees. It also forged friendships, and 30 years after the company was established, a party was held, bringing together everyone who could possibly attend. According to Santamäki, it was also great to see what organisational support meant for R&D.

Rebellion spirit and no-brainers

Today, Santamäki works as a partner at Voima Ventures. If he still would need to do research on something, he would continue with communications and develop a new kind of media – following this idea, he would not run out of things to study.

Santamäki spends a lot of time thinking about the nature of technology. Earlier, when it came to technology, people always used to want more, bigger and better. Now we are starting to lose sight of technology. We no longer even consider many technologies as technology at all, as they have become so commonplace. However, “the good old times” are not real. The development is continuously going in a good direction.

“I’ve always been fascinated about a certain spirit of rebellion, in other words, the moment when you realise that a specific change is approaching. If there are dying giants in the sector, innovations can act as real game changers.”